Does Being Detained For No Probable Cause Go on Your Record?

While a police report is created and that is considered public record, being detained without an arrest does not appear on a person’s record for purposes of employment or housing.

Table of Contents

One might inquire whether being detained goes on your record.

Figuring out whether or detainment goes on your record largely depends on whether the individual was arrested. This is because an officer can detain someone and then make an arrest, or they detain someone for investigative purposes and then let the person go.

If detainment leads to an arrest, the charge will go on a person’s record unless they’re a juvenile or it’s been sealed or expunged — even if the person was innocent and the charges were dropped or dismissed.

But if the individual was detained and released after a short investigation, a police report is made to document the interaction with law enforcement and depending on the agency or jurisdiction, the police report could show up on your record through public criminal records, court documents or police reports.

The following guide explores the intricacies of what’s considered detainment, how and when police reports show on public records, your rights when it comes to being detained, and more importantly, how to be 100% sure detainment isn’t on your record.

The difference between being arrested or detained lies in the amount of information or evidence that officers have at the time of the stop, and how long a person can be held once stopped by police. More details on each of these considerations is provided below.

Also, it’s vital to understand that the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects anyone within the US from unreasonable search and seizure, and this covers investigatory stops or being detained by the police. Which means police must have reasonable suspicion a crime has been committed or is about to be committed before stopping someone on the street or pulling over a motor vehicle.

Overall, it’s a complicated issue, and the information below takes some of the mystery out of the process.

Source: Administrative Office of the United States Courts1

It can be a scary experience being detained by police, and many people wonder how long law enforcement can hold someone before giving them a citation, summons or arresting the person.

The United State Supreme Court ruled on temporary stops or investigatory stops of person’s suspected of committing a crime or about to commit a crime in the case of Terry vs Ohio which gives law enforcement the right to stop someone for a limited amount of time to establish their identity and discover if their suspicions have foundation, known as establishing probable cause.

Source: United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs2

When looking at investigatory stop laws, it’s important to know the definition of reasonable suspicion. Reasonable suspicion offers the least amount of authority over someone, and a police officer must reasonably believe (have reasonable suspicion) a person he or she is stopping or holding for questioning has committed a crime or infraction.

The officer must also be able to reasonably articulate, clearly state, the suspicion as justification for the stop. In other words, police officers cannot just stop people based on a hunch.3

This means law enforcement must respond to a call regarding a crime to stop and question someone who fits the description of the suspect, or is driving a vehicle that matches the description of a vehicle involved in a criminal offense. For example, if law enforcement receives a report of hit and run, officers can pull over vehicles that resemble the suspect vehicle in the area, but may not stop every vehicle they encounter.

Law enforcement can also detain certain individuals for safety reasons such as juveniles who may be out after curfew, or people who pose a risk to themselves due to intoxication. There are other factors that can cause someone to be detained including stop and frisk laws that will be detailed further in the article.

Ultimately, the key words regarding getting detained is reasonable suspicion.

Once someone is detained, the risk of being arrested increases, but there are certain thresholds of proof that must be met before being detained turns into being arrested.

For example, a person can be detained under reasonable suspicion they have committed a crime or are about to commit a crime, but this is not enough grounds to arrest someone because evidence is lacking.4

Being arrested means there must be probable cause that a crime has been committed and the suspect is likely the one who committed the crime. Probable cause requires a higher level of evidence than reasonable suspicion. In addition, a person can be released from police after being detained only to find they are wanted later on in the investigation as a suspect.

For example, someone is being detained as a suspect in a larceny from a business because they fit the description of the person who committed the crime or their vehicle fits the description of the vehicle used to flee the scene. In the course of questioning the person, law enforcement discovers some of the stolen property on them or in their vehicle.

At this point, reasonable suspicion has been elevated to probable cause since they went from resembling the physical description of the suspect to being in possession of stolen property.

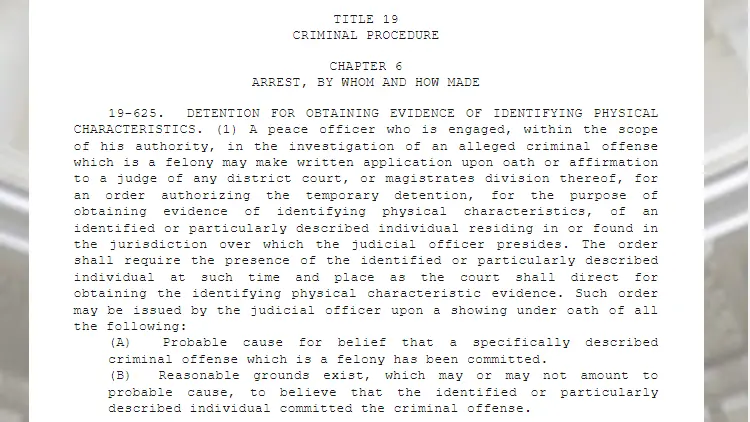

Source: Idaho State Legislature5

Or, the officer can detain someone until an employee at the store arrives and makes a positive identification or says they are not the person who stole from the business, or for law enforcement to transport them back to the location for an identification.

If the worker makes a positive identification, this will elevate the matter based on evidence they were most likely the person who stole from the store, establishing probable cause for detainment to lead to arrest.6

Law enforcement can only hold the person until they are able to establish the identity of the person and get enough evidence to establish probable cause or rule them out as a suspect but the amount of time can vary from state to state.

When the encounter ends with law enforcement letting the person leave without giving them a ticket, citation or summons, the only record of the encounter will be the police report.

If the encounter results in the person being arrested, the record of arrest also becomes public record, and the person is afforded the right to call a family member, attorney or bail bondsman to help with their release.

Additionally, if someone has been arrested after being detained, a friend or family member can call the local police department or jail to see if the individual is being housed in that facility or find out why they were arrested.

Each state has some sort of public records act which makes police reports when a person is detained, such as a traffic stop, public as well even when charges are not filed.

The only exceptions to police reports being public record is when they are part of a large investigation that has not been resolved in court and release of the record can compromise the investigation, or when it involves protected health information such as transporting someone to a treatment facility or hospital.

In short, police reports of people being detained are considered public record and a person can find out someone was detained by police by submitting a records request to the local police department or sheriff’s office that handled the matter. This does not mean, however, that the existence of a detainment record can be used against a person.

Arrests and convictions can have a negative impact on a person’s life when applying for employment, housing, or licensing background checks worry of detainment showing can cause undue distress.

The police report detailing the encounter is a public record that can be accessed through the records department at the agency where the officer works; however, the good news is police reports typically do not appear on background checks unless being detained led to enough probable cause to cause the person’s arrest and later conviction.

To be more specific, simply being detained will not appear on screenings such as level 1 background checks which are name-based and are primarily concerned with criminal convictions rather than non-convictions or pending matters.

These are the most common type of background checks for housing or employment purposes, so the record of being detained should have little to no impact on this type of background check.

Incidents of being taken into protective custody will also not show up on a background check since they may contain information about medical or mental health conditions that are protected by law from disclosure.

Release of information on a background check is subject to the state and federal laws surrounding arrest and criminal records which includes police reports that result in non-convictions such as being detained but not charged. For example, Fair Credit Report Act regulations prohibit release information on non-convictions that are more than seven years old which includes investigatory stops that did not result in charges or convictions.

Source: United States, Federal Trade Commision7

If a person has been detained and is subsequently charged with an offense either while being questioned by the police or at a later date, the pending charge will appear on a background check.

The best way to see if being detained will show up on a background check is to run a personal screening through the your local or state law enforcement agency, or third-party providers.

Some state agencies or courts also allow people to run a free criminal background check on themselves online or at the local courthouse and is another way to see if being detained shows up on the public records search.

This will allow someone to see if that traffic stop or that time law enforcement stopped them on the street to ask them questions shows up on a report through the official state agency that provides screenings or commercial background check sites that provide screenings.

In addition to rights surrounding background checks, it is necessary for a person to know their rights when they are detained to make sure they do incriminate themselves.

Another point to consider is what happens when a person is subject to a citizen’s arrest. Simply put, a citizen’s arrest occurs when a private citizen, not a sworn law enforcement officer, takes a person into custody or detains them after witnessing them commit a crime.

While the laws vary somewhat from state to state, each state does allow for some form of citizen’s arrest or complaint process to catch offenders. For example, in Alaska under statute 12.25.030, a private citizen may arrest someone when they witness them commit a crime, a felony has been committed and the person has reasonable cause to believe the subject was the offender.

The person must also be seen by a judge or magistrate without delay in the event of a citizen’s arrest at which the formal complaint is filed. This makes a citizen’s arrest the same as a law enforcement arrest, which does go on a person’s record.

In Maine, Title 17-A, Part 1, Chapter 1, Section 16 also gives authority to private citizens to perform a citizen’s arrest under specific circumstances such as witnessing the person committing or attempting to commit a murder, committing a class A, B or C crime in the citizen’s presence, committing a crime on the property of the arresting citizen. In short, the person must witness the crime to perform a citizen’s arrest in Maine.

Source: Maine State Legislature8

When making a citizen’s arrest, the person only has the right to restrict the movement of the individual, not perform a search of their person or property. They also cannot take evidence into custody.9

In short, a citizen’s arrest can have the same power as a law enforcement arrest, meaning it can and does appear on a background check.

However, no matter who made the detainment or arrest, it’s important to understand your rights surrounding how long you can be detained, when they must read you your rights, and how to handle the interaction overall.

In popular TV cop shows and movies, individuals are often shown being informed of their Miranda rights upon being taken into police custody, but legally, law enforcement is only obligated to advise a person of their Miranda rights when they are arrested and subjected to interrogation while in custody. This creates a slippery slope when detainment is part of the equation because being detained is not the same as being arrested, and questions asked while being detained are not considered an interrogation.10

It is a good idea, however, when being detained to invoke your right to remain silent and request legal representation since detainment can, and sometimes does, lead to an arrest.

Going back to Terry vs Ohio, law enforcement must establish reasonable suspicion to even stop someone in the first place, and the officer cannot detain a person longer than necessary to continue the stop, but what constitutes a reasonable amount of time can vary based on the reason for the stop and the state where the stop occurs.

Most investigatory stops span less than an hour with the average time being 20 minutes, but officers are not limited to that time frame.11

Source: Hawai‘i State Legislature12

Therefore, law enforcement can detain a person long enough to establish the person’s identity, ask questions (which the subject has the right to refuse to answer), and determine if probable cause has been established or not. If someone asks law enforcement if they are free to leave and the officer says they can, continuing to stay on the scene and interact with the officer makes the interaction voluntary.13

For convenience, we’ve linked the statute in each state around investigatory stops (sometimes call stop and frisk which will be discussed further below), and the maximum amount of time police can detain someone without charging them with a criminal offense or arresting them:

| State | State Law | Maximum Time a Person Can Be Detained (On Site or In a detention facility) Without Being Arrested or Charged* |

| Alabama | 15-5-30 | Up to 48 hours |

| Alaska | 12.50.201 | Up to 72 hours |

| Arizona | Title 13 | Up to 48 hours |

| Arkansas | Criminal Procedure Rule 2.1 | Up to 48 hours |

| California | Penal Code 825 | Up to 48 hours |

| Colorado | 16-3-103 | Up to 48 hours |

| Connecticut | Section 9 of state constitution | Up to 72 hours |

| Delaware | 11-1910 | Up to 2 hours |

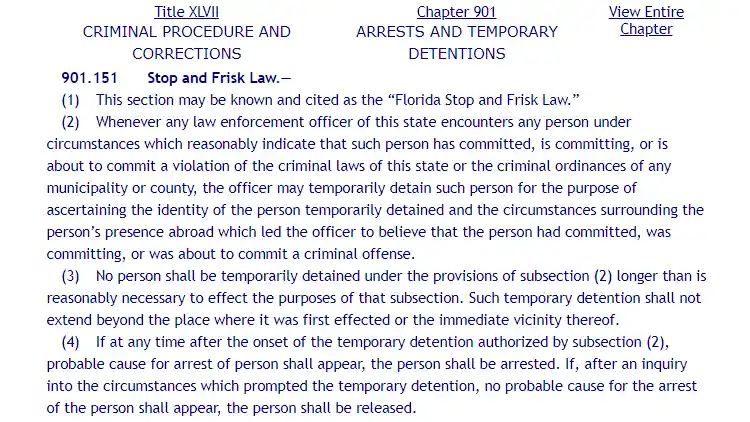

| Florida | 901.151 | Up to 33 days |

| Georgia | Title 17, Chapter 4 | Up to 48 hours |

| Hawaii | 803-4 | Up to 48 hours |

| Idaho | 19-625 | Up to 3 hours |

| Illinois | 725 ILCS 5/107-14 | Up to 48 hours |

| Indiana | 35-40-4-7.3 | Up to 72 hours |

| Iowa | Chapter 808 | Up to 48 hours |

| Kansas | 22-21402 | Up to 48 hours |

| Kentucky | 235-310 | Up to 72 hours |

| Louisiana | CCRP 215.1 | Up to 48 hours |

| Maine | 25A-105 | Up to 72 hours |

| Maryland | 4-206 | Up to 72 hours |

| Massachusetts | 424.1 | Up to 72 hours |

| Michigan | 111 (10/14) | Up to 72 hours |

| Minnesota | 626.8471 | Up to 72 hours |

| Mississippi | 95-15-1 | Up to 48 hours |

| Missouri | 84-710 | Up to 24 hours |

| Montana | 46-5-401 | Up to 72 hours |

| Nebraska | 29-829 | Up to 72 hours |

| Nevada | 171.123 | Up to 72 hours |

| New Hampshire | 595-A:10 | Up to 24 hours |

| New Jersey | 2C:21-29 | Up to 48 hours |

| New Mexico | 29-21-2 | Up to 72 hours |

| New York | 140.50 | Up to 24 hours |

| North Carolina | 20-29 | Up to 8 hours |

| North Dakota | 29-29-21 | Up to 72 hours |

| Ohio | 2921.29 | Up to 48 hours |

| Oklahoma | State Constitution Section 11-30 | Up to 72 hours |

| Oregon | 131.615 | Up to 48 hours |

| Pennsylvania | 34-904(b) | Up to 48 hours |

| Rhode Island | 31-21.5-5 | Up to 2 hours |

| South Carolina | 17-13-170 | Up to 72 hours |

| South Dakota | 32-33 | Up to 72 hours |

| Tennessee | 39-16-602 | Up to 48 hours |

| Texas | Title 8, Chapter 38 | Up to 72 hours |

| Utah | 77-7-15 | Up to 72 hours |

| Vermont | Title 24, Chapter 059 | Up to 72 hours |

| Virginia | 52-30.2 | Up to 48 hours |

| Washington | 46.61.020 | Up to 72 hours |

| West Virginia | 30-29-10 | Up to 48 hours |

| Wisconsin | 968.24 | Up to 48 hours |

| Wyoming | 7-2-102 | Up to 72 hours |

*Although states can hold someone without charges for several hours, most encounters only last a few minutes as officers establish the person’s identity and rule out criminal activity.

Popular media uses the phrase probable cause when showing things such as traffic stops or investigatory stops, but this can be confusing because probable cause is not the threshold for an investigatory stop or detainment, but is the threshold for an arrest.

Ultimately, law enforcement does have the right to stop someone based on reasonable suspicion which does not rise to the level of probable cause; however, law enforcement is not allowed to detain a person for an unreasonable amount of time.

What this means is law enforcement cannot continue to detain a person based on reasonable suspicion alone. The sole purpose of police detention is to gather information, and at any time, the subject can ask if they are free to leave. If they are being detained, the officer must articulate, meaning clearly state, what that reasonable suspicion led to the stop.

However, there are still times where you can be charged without knowing since the law enforcement agency can press charges later in the investigation based on new evidence.

Source: Pennsylvania General Assembly14

For example, a person is stopped by law enforcement in a traffic checkpoint because someone has escaped from a nearby jail or prison. Law enforcement can stop vehicles within the vicinity of the detention center to make sure that the escapee isn’t inside one of those vehicles.

Once satisfied the person is not in someone’s car, they must let the person leave.

Another example is when someone matches the description of a person who has committed a robbery or other crime, so law enforcement can detain the person for a short period of time to determine if the person stopped is the offender. This can include waiting for a witness to make an identification, or transporting the person to the business or area to view video surveillance footage to rule out the person detained.

A third example could be law enforcement stops and searches a person believed to be unlawfully carrying a weapon, and this reasonable suspicion is based on the officer’s training and laws in the state.

Law enforcement cannot continue to detain someone if probable cause is not established and reasonable suspicion no longer applies.

The table above shows the maximum amount of time a law enforcement can detain a person without probable cause before either having to file formal charges or releasing the individual. The more serious the offense, the more likely the person will be detained by police longer.

Another common scene in popular media is law enforcement stopping people and patting them down to check for weapons.

This is referred to as a stop and frisk, but there are some rules that must be followed in these types of stops as well. In addition, not every state allows this type of investigatory stop.

Source: Florida State Legislature15

There are three elements that must be met for a stop and frisk investigatory detainment. These element are:

The following states allow stop and frisk investigatory detainment by law enforcement:

*The states in the list above marked with asterisks (*) can charge someone with violating a criminal offense for failure to provide identification. In these stops, officers can use detainment as a means to find someone’s middle and full name, or aliases to establish identity and rule the person out as a suspect.

Also called stop and identify states, when someone is detained by police in these states they may be by law to at least provide identification; however, they are not obligated to answer any additional questions.17

In other states, the wording of the statute can determine if law enforcement can escalate the matter from detainment to arrest based on the person’s compliance or non-compliance.18

Stop and frisk or stop and identify, or reasonable suspicion someone has committed a crime or is about to commit a crime is not the only reason law enforcement may detain someone. Law enforcement is also tasked with protecting individuals and can detain someone based on this obligation.

In addition to detaining individuals suspected of committing a crime, law enforcement has a duty to protect citizens from themselves and others when under the influence.

This means law enforcement can detain someone until they are sober or until a responsible, sober agrees to take responsibility for the person. Not every state has a public intoxication law that allows police to detain someone under the influence, but in states that do, a person can be held until they are not showing signs of impairment or 72 hours whichever occurs first.

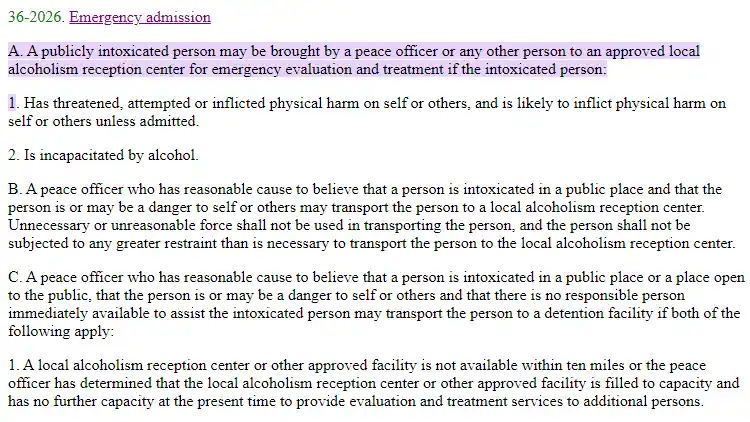

Source: Arizona State Legislature 19

Certain criteria must be met before a person can be held until sober in states that allow the practice, including the following:

The table lists the states with public intoxication laws and what authority law enforcement has to detain someone who is in public under the influence based on state statute:

| State | Public Intoxication Law | What Law Enforcement Can Do |

| Alabama | 13A-11-10 | Law enforcement can arrest someone for public intoxication. |

| Alaska | 47.37.170 | Public intoxication is not a criminal offense, but law enforcement can transport individuals who are intoxicated in public to a sleep-off facility until sober. |

| Arizona | 36-2026 | Law enforcement may transport a person publicly intoxicated to an alcohol reception center to hold for 24 hours. |

| Arkansas | 5-71-212 | Law enforcement can arrest someone for public intoxication if there is not a sober companion to turn them over to. |

| California | 647 | Law enforcement can transport a person intoxicated in public to a treatment facility to be held for up to 72 hours for evaluation and treatment. |

| Florida | 856.011 | Law enforcement may transport a person intoxicated in public to their home or to a treatment facility to detox. |

| Georgia | 16-11-41 | Law enforcement can arrest someone for public intoxication. |

| Indiana | 7.1-5-1-3 (2020) | Law enforcement may transport a person who is publicly intoxicated to the home of a sober friend or family member, or may take the person to a treatment facility for detox. If these are not available options, law enforcement can detain the person in jail until sober. |

| Iowa | 125.34 | Law enforcement has the option to transport a person publicly intoxicated to a treatment facility for detox, or hold the person in custody until they sober up if a treatment facility is not available. |

| Kentucky | 222.202 | Law enforcement can arrest someone for public intoxication. |

| Maryland | 19-101 | Law enforcement may take an intoxicated person to a detox center for evaluation and treatment. |

| Michigan | 330.1276 | Intoxicated person can be detained up to 8 hours or until they can be transferred to an appropriate treatment facility when deemed a danger to themselves or others due to public intoxication |

| Mississippi | 97-29-7 | Law enforcement can arrest someone for public intoxication. |

| New Jersey | 26:2B-8, 26:2B-16 | Law enforcement must transport a publicly intoxicated person to an approved treatment facility. |

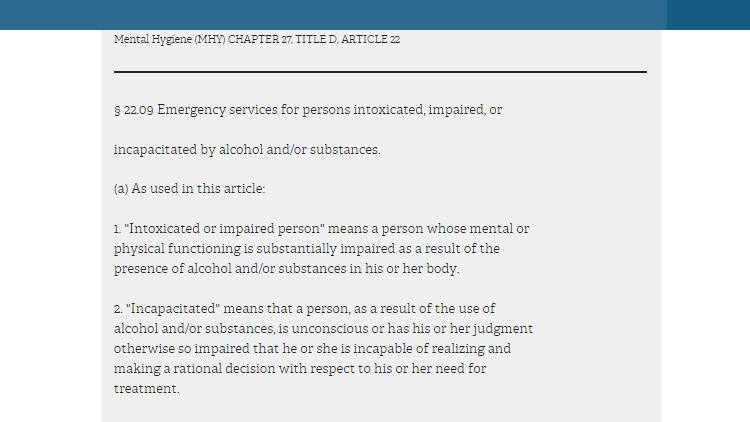

| New York | 22.09 | An intoxicated person can be held up to 48 hours or until they sober up and are no longer a danger to themselves or others. |

| North Carolina | 122C-301 | Law enforcement may detain someone long enough to transport them to their home where a sober adult is located, or to the home of a sober friend or family member to release the person to. |

| North Dakota | 5-01-05.1 | Law enforcement may take an intoxicated person to their home, the home of a sober friend or family member, the emergency department of the hospital, a treatment facility or jail until the person is sober. |

| Ohio | 2935.33 | Law enforcement can transport an intoxicated person to a detox or treatment center to be held for up to 48 hours. |

| Oklahoma | 43A-3-428 | Law enforcement can transport an intoxicated person to their home or a treatment facility but only with the person’s consent. |

| Oregon | 430.399 | Law enforcement may transport a person publicly intoxicated to a treatment facility for up to 48 hours or a sobering facility for 24 hours. If no facility is available, the person can be detained in jail until sober |

| Pennsylvania | 18 PACS 5505 | Law enforcement can arrest someone for public intoxication. |

| South Carolina | 16-17-530 | Law enforcement can arrest someone for public intoxication. |

| Tennessee | 33-10-203 | Public intoxication is approached with treatment instead of punishment, but law enforcement can only transport a person to a treatment facility with their consent. |

| Texas | 14.031 | Law enforcement may detain a person until they are sober or can be released to a responsible, sober adult or place the person in a detox center. |

| Virginia | 18.2-388 | Law enforcement may transport the person to an approved substance abuse treatment facility with the person’s consent. |

| Washington | 70.96A.190 | Law enforcement may hold a person up to 8 hours or until they can be transported to an approved treatment facility. |

Hold until sober laws are designed to provide publicly intoxicated individuals a safe environment in which to sober up without harsh criminal penalties, and in the state above can help the resident living here get treatment rather than a criminal record.

When it comes to protective custody and if detainment goes on your record, police departments are required to make a report of the incident, this is not as likely to show up on public records as it may contain protected health information such as transportation to a treatment facility or hospital emergency department.

In addition, sometimes a person is taken into custody following a wellness check just long enough to transport the individual to a treatment facility or hospital, or to release the person to a responsible adult who will care for the individual when they cannot care for themselves.

While there will be a police report of the incident, wellness checks typically don’t show on your record or a background check.

Next, it is important to know what happens after a person is detained and the effect it can have on a person’s future.

Source: New York State Senate21

Being detained by police can be very stressful, but there are steps a person can take to preserve their rights while avoiding escalation during the encounter. These include the following:

Being stopped by the police can cause a great deal of distress to a person, but it does not have to result in negative consequences.

In summary, determining whether or not detainment goes on your record depends on if you were arrested — arrests will always appear on your record and detainment that doesn’t lead to result won’t show up on background checks although they can be requested through the law enforcement agency who made the stop.

While a police report is created and that is considered public record, being detained without an arrest does not appear on a person’s record for purposes of employment or housing.

When being detained does not result in a criminal charge or arrest, the department may automatically destroy the record after one to two years have passed with no action. If it is an investigatory report and the statute of limitations has expired, a request can be made to destroy the record. If being detained led to arrest and conviction or non-conviction that is eligible for expungement, once an order to expunge is entered by the court, the record must be destroyed or sealed.

The amount of time a person can be detained varies from state to state with some allowing up to 72 hours before a person must be released or charged and arrested. The majority of investigatory stops last around 20 minutes. Law enforcement can detain someone based on reasonable suspicion only, but they must be able to articulate that reasonable suspicion, which is a lesser degree of certainty than probable cause, to make the stop and hold the person for questioning.

1 Administrative Office of the United States Courts. (n.d.). What Does the Fourth Amendment Mean? Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/what-does-0#:~:text=The%20Constitution%2C%20through%20the%20Fourth,deemed%20unreasonable%20under%20the%20law.>

2 U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. (1983). Terry vs Ohio. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/terry-vs-ohio>

3 Reasonable Suspicion. (n.d.). Search and Seizure. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <http://www.searchandseizure.org/reasonablesuspicion.html>

4 Reasonable Suspicion and Probable Cause – Different Meanings. (n.d.). Kearney, Freeman, Fogarty & Joshi, PLLC. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://www.kffjlaw.com/library/how-reasonable-suspicion-and-probable-cause-are-defined.cfm>

5 Idaho State Legislature. (2022). Idaho Statutes, Title 19, Chapter 6, Section 19-625. Detention For Obtaining Evidence Of Identifying Physical Characteristics. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://legislature.idaho.gov/statutesrules/idstat/title19/t19ch6/sect19-625/>

6 Stowe, R. (2022, October 31). Detainment vs. Arrest: Knowing The Difference. Stowe Law Firm, PLLC. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://www.stowelawfirmnc.com/detainment-vs-arrest-how-to-know-the-difference/>

7 United States Federal Trade Commision (2023, June 5). Fair Credit Reporting Act. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/statutes/fair-credit-reporting-act>

8 Maine State Legislature, Maine Revised Statutes. (2022, September 28). Title 17-A: Maine Criminal Code, Part 1: General Principles, Chapter 1: Preliminary. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://legislature.maine.gov/statutes/17-A/title17-Asec16.html>

9 Are Police Still Required to Read Miranda Rights? (2022, August 7). Hulnick, Stang, Gering & Leavitt, P.A. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from <https://www.hulnicklaw.com/blog/2022/august/are-police-still-required-to-read-miranda-rights/>

10 When Can Police Detain You: A Guide To Being Detained [2023]. (n.d.). Law Office of Jordan Marsh. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://jmarshlaw.com/detain-or-arrest-probable-cause/>

11 Terry Stop and Frisks Doctrine and Practice | U.S. Constitution Annotated | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Law.Cornell.Edu. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-4/terry-stop-and-frisks-doctrine-and-practice>

12 Hawai‘i State Legislature. (2023). §803-4 On suspicion. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/hrscurrent/Vol14_Ch0701-0853/HRS0803/HRS_0803-0004.htm>

13 Stop and Frisk. (n.d.). Office of Justice Programs. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/stop-and-frisk-0>

14 Pennsylvania General Assembly. (2010). Consolidated Statutes. Title 34. § 904. Resisting or interfering with an officer. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/LI/consCheck.cfm?txtType=HTM&ttl=34&div=0&chpt=9&sctn=4&subsctn=0#:~:text=%2D%2DWhen%20an%20officer%20is,%2C%20menace%2C%20flight%20or%20obstruction>

15 Florida State Legislature. (2022). Stop and Frisk Law. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0900-0999/0901/Sections/0901.151.html>

16 What is a Citizen’s Arrest? | Los Angeles Criminal Defense Lawyer. (n.d.). Stephen G. Rodriguez & Partners. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from <https://www.lacriminaldefenseattorney.com/legal-dictionary/c/citizens-arrest/https://www.criminaldefenselawyer.com/crime-penalties/federal/public-intoxication.htm>

17 Stop and ID States 2023. (n.d.). Wisevoter. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://wisevoter.com/state-rankings/stop-and-id-states/>

18 Stop and identify statutes. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stop_and_identify_statutes>

19 Arizona State Legislature. (2023). 36-2026. Emergency admission. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://www.azleg.gov/ars/36/02026.htm#:~:text=36%2D2026%20%2D%20Emergency%20admission&text=A.,1>

20 Portman, J. (n.d.). Public Intoxication Laws and Penalties. CriminalDefenseLawyer.com. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://www.criminaldefenselawyer.com/crime-penalties/federal/public-intoxication.htm>

21 New York State Senate. (2021, October 8). SECTION 22.09. Emergency services for persons intoxicated, impaired, or incapacitated by alcohol and/or substances. Retrieved June 6, 2023, from <https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/MHY/22.09>

22 Know Your Rights | Stopped by Police | American Civil Liberties Union. (n.d.). ACLU. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from <https://www.aclu.org/know-your-rights/stopped-by-police>

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.